This installment of the Science of Kindness was reprinted with permission from Envision Kindness.

In my exploration of how kindness connects people, it has become pretty clear to me that being kind to someone else uplifts both people and creates a positive link between them. Many times, I have read how people feel good after they help someone through volunteering, or even holding a door open—and I've felt it myself.

If persuaded to explain why it feels good, it is clear that helping someone else (or simply witnessing kindness) sets off a series of changes in the brain similarly to the release of endorphins, the internal opiates. Spiritually, of course, helping someone is the right thing to do. The biological connection between my spiritual understanding and how I feel suggests that nature has wired me to do so; my body is reinforcing/rewarding these "right things" with pleasurable sensations. Similarly, the receiver also feels good because he or she has been acknowledged or valued.

Acts of kindness therefore create meaningful connections between people. It is part of what I have called the "kindness-connection cycle", in which acts of kindness connect the giver and receiver to one another.

The focus of this class is the last arc of the kindness-connection cycle, which states that meaningful connection increases kindness in turn. The central idea is that when we truly understand how each of our lives is intertwined with so many others, kindness, compassion, and collaboration flow much more naturally.

Although we are unique individuals, our lives are part of a dynamic and vibrant larger network. What each of us does in that network influences many others and vice versa—i.e., we are in this together.

There are many different examples of how we are connected to each other, such as being connected through economics, interpersonal interactions, workplace, community, family, etc.

One overlooked aspect of being connected to each other, however, is the common biology that we share. For example, blood courses through our arteries and veins before being filtered by the kidneys and pumped by a heart which beats approximately 100,000 times every day.

There are many other systems that, with slight variation, function the same way in healthy people, such as the regulation of blood sugar, blood pressure, and immune responses – and although we may differ in outward appearance (height, body, facial shape, or skin color), our bodies still generally work the same way.

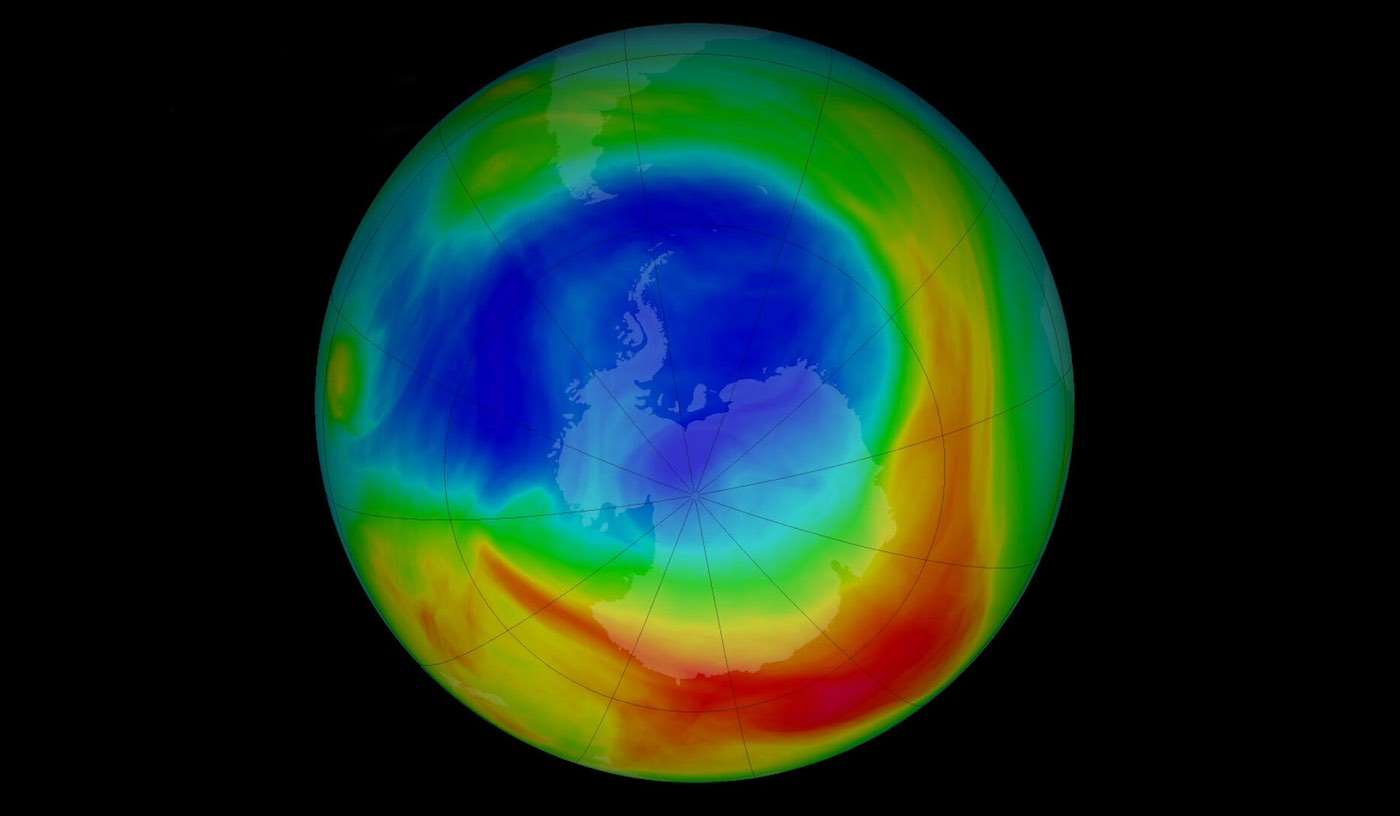

Beyond the systems that we have in common, we also actively share our biological lives with each other. Let's focus on oxygen, one of the most abundant elements on the planet that is absolutely critical for our survival. Inhaled oxygen (O2) is required to use calories and convert them into energy fuel for our cells; this process then produces carbon dioxide (CO2) which we exhale as a byproduct. Life is not possible without oxygen.

Let's imagine that you and I are hiking a trail in the woods and we stop to admire a vista. Much of the oxygen we are inhaling is probably produced by the trees and plant life—yet how did the tree make oxygen? As other hikers have gone through the forest, the trees—powered by sunlight—absorb the carbon dioxide that is exhaled by the hikers so they can transform it into cellulose. O2 is then released from the CO2 that the trees have absorbed, thus continuing the oxygen cycle between the hikers and the trees.

This means that the oxygen I breathe in to survive was used by someone else in the past to help them live as well—and it will also be used by someone else in the future.

As oxygen is constantly being recycled, and each person needs about 500 liters of oxygen each day, multiple authors have speculated on how we may have inhaled the same oxygen molecules as Julius Caesar, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., or any other historical figure.

The bottom line: all of our lives depend on sharing, and this sharing extends across time.

This example also illustrates how we are critically connected to trees and nature. Without plant life, oxygen wouldn't be produced and carbon dioxide wouldn't be cleared—and since roughly half of the oxygen on Earth comes from phytoplankton in the oceans, this means that our oxygen-dependent lives are also tied to the sea. Phytoplankton, in turn, depend on waste and motion from larger sea creatures—such as whales.

When something disrupts these cycles, like deforestation or whale hunting, we share in the problems that follow. When we protect and nourish them, however, we honor their significance and are rewarded for it.

What goes around, comes around. Life is much more about cycles rather than straight lines. Oxygen is just one of many examples that, by the nature of our shared biology, we are connected to one another. The same is true for nitrogen, water, iron, and a host of other biologically essential factors that are recycled by other life forms. This gets more complex once we include the interactions of insects and animals that are necessary to keep the fabric of our interwoven network healthy and vibrant.

So what does this teach us? It tells us that our lives are more intimately connected than we might ever have thought. On a basic level, it teaches that sharing (kindness and cooperation) is actively required for living beings to survive.

Beyond that, we are deeply connected by the oxygen cycle in a reciprocating, cooperative way. Without trees and greenery, we would not survive—and as those systems depend on carbon dioxide to survive, we sustain them in turn. Short-sighted selfishness that overuses or abuses a component of the cycle will come back around to affect us.

But the cycle is fragile; without us doing the right thing to responsibly maintain our part of a mutually nourishing cycle, it can fail. Doing the right thing honors two principles: being kind to and respecting the roles of other members of the cycle, and being kind to ourselves to sustain our own well being.

The eminent conservationist John Muir wrote: "When one tugs at a single thing in nature, you find it attached to the rest of the world." That is, we are all connected.

Interested in learning more about the science of kindness and its role in your life? Visit EnvisionKindness.org to learn more.

Be Sure And Share This Inspiring Segment Of "The Science Of Kindness" With Your Friends On Social Media – Photo by Gabriela Palai, CC

Be the first to comment