Doug Lindsay had just entered his senior year at Rockhurst University in Kansas City, Missouri when he came home from his first day of class only to be plunged into a real-life "final project" that took him 13 years to finish.

The assignment: to find the origin and cure for a mysterious condition that had plagued the bodies of his family for generations, and now was targeting his own.

He was only 21 that day when the room began to spin around him and he collapsed onto the dining room table in 1999.

As a biology major, Lindsay had seen himself becoming a biochemistry professor—or maybe even a writer for "The Simpsons." He was a former high school track athlete, and he was poised to finish the year and earn his degree.

However, Doug admitted to always wondering if the debilitating condition that sidelined his mother and aunt in their early adult years would eventually affect him, too. "When I called my mom that night to tell her I needed to drop out (of college), we both knew," he told CNN.

His mother had gotten weaker until she couldn't pick him up when he was just 18 months old. By the time her son was four, she couldn't walk. She lived on for decades, but she was too frail to do much beyond submitting to years of tests that never confirmed any condition.

As his ability to stand and walk worsened, he realized that physicians and specialists were no more enlightened than when they'd tested his mother and aunt (who was also sidelined by the mystery condition). When one puzzled doctor finally told Doug that he should see a psychiatrist, he knew he would have to unravel the family "curse" on his own.

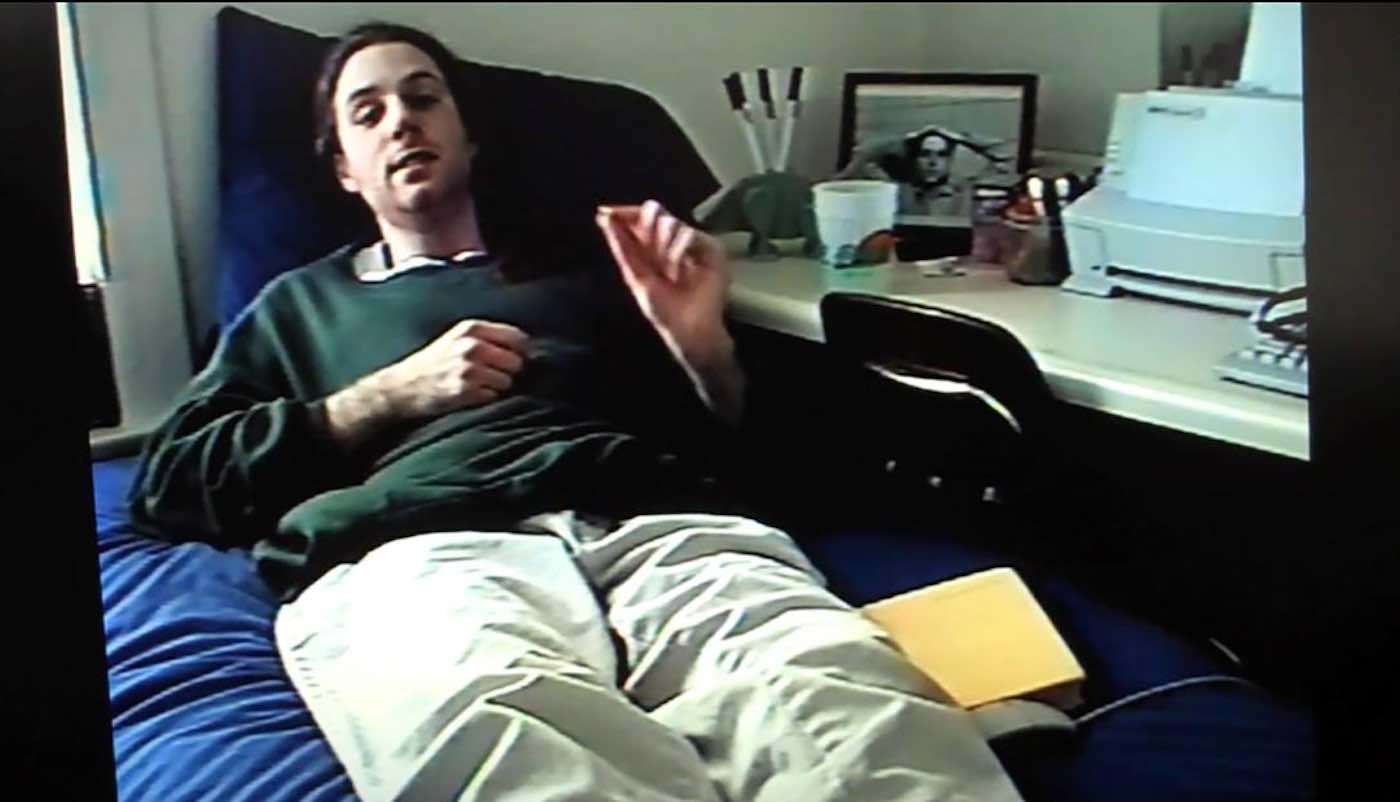

He worked through the clues in his living room from the hospital bed where he stayed 22 hours a day. He began by pouring over medical books he'd collected, and then recalled a 2,200-page endocrinology textbook he'd picked up next to a trashcan on campus. At the time, he was hoping it would hold the secret to what was wrong with his mother. As he read through the book a second time, a passage captured his attention and gave him an idea.

Doug's mother suspected her weakness was related to her thyroid somehow, but this book suggested adrenal gland problems can share the same symptoms with thyroid issues. He then formed a bold hypothesis—that there existed an entire class of diseases of the nervous system still undiscovered by medicine.

He knew he needed to find a courageous doctor interested in pursuing new discoveries. He found that partner in Dr. H. Cecil Coghlan, a medical professor at the University of Alabama–Birmingham.

Coghlan thought the young student might be onto something—so he helped Doug begin an IV protocol of noradrenalin to counter any excessive adrenalin his glands might be producing. The drug, usually prescribed to critically ill patients to raise blood pressure, worked enough to get him walking again for short periods around the house—and he was hooked up to the bag of liquid continually for six years.

But why was his body producing so much adrenaline in the first place? Dr. Coghlan proposed an adrenal tumor might be the culprit, but three scans all came up negative. Undeterred, Doug pored through the literature and came to believe that something else could be acting like a tumor, causing his glands to misbehave.

Be the first to comment