Archeologists Confirm Oldest Viking Ship Burial in All Scandinavia-Could Rewrite the Viking Age

It dates back so far, there's a technical question about whether or not one can even call it a Viking ship burial

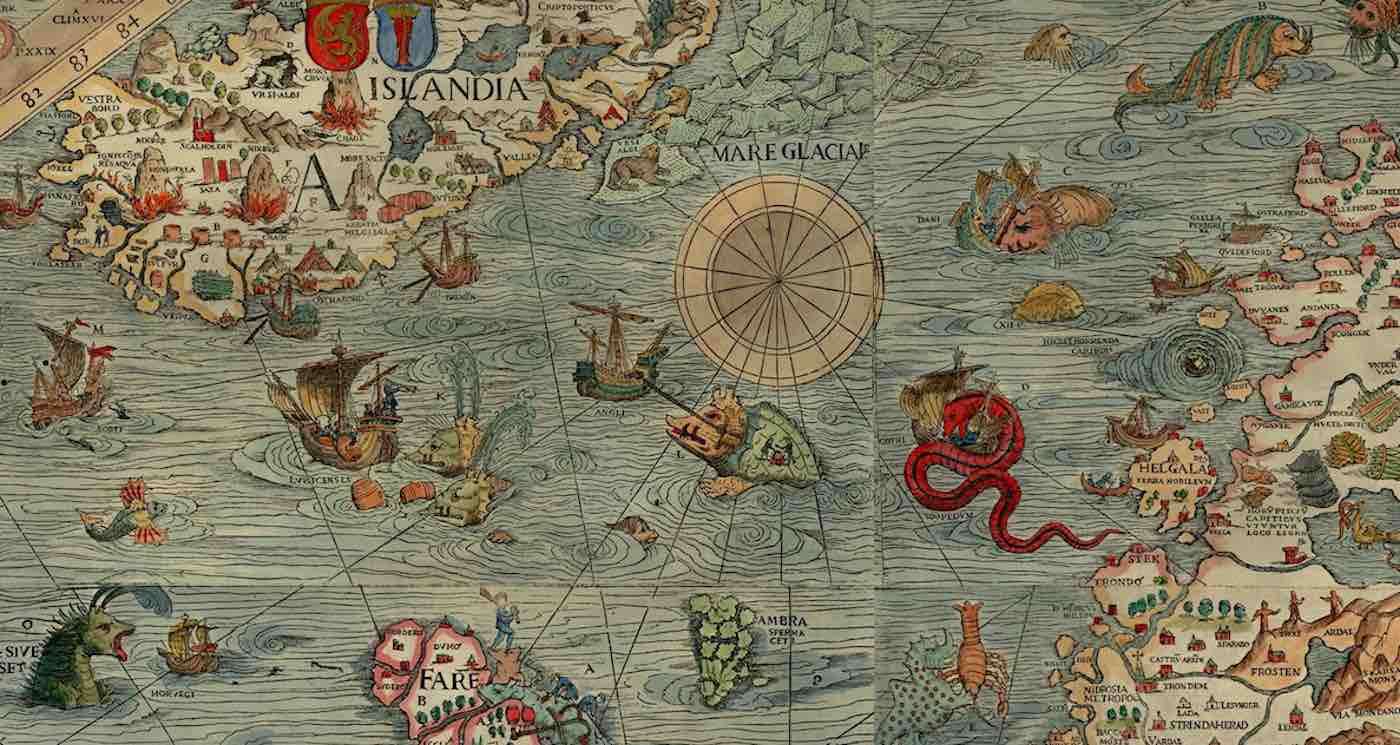

Everyone knows that our ancestors believed the seas and oceans were the domains of monsters, but the extent of this fear, as depicted in early Renaissance maps, is striking to behold.

As early as the 9th century, Arab historians such as Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī, who compiled first-hand accounts of sailors from China and India, knew to discount or ignore their stories of sea serpents.

This evidently didn't take hold until later in scholastic traditions of Europe, because as late as the 15th century, maps were still covered in images of "sea swine," "sea orms," and "pristers."

The map above is one of the most famous examples of the fear that Europeans clung to during the Renaissance. Initially published in 1538 by Swedish ecclesiastic Olaus Magnus, the Carta Marina was one of the earliest maps to depict Scandinavia with such a richness of place names.

According to author Edward Lynam writing in 1949, Magnus drew from a variety of ancient sources including Ptolemy's map in Geographia, and contemporary sources such as the work of Astronomer Jacob Ziegler. In addition to cartographic sources, Magnus also relied on the descriptions of sailors and his own observations.

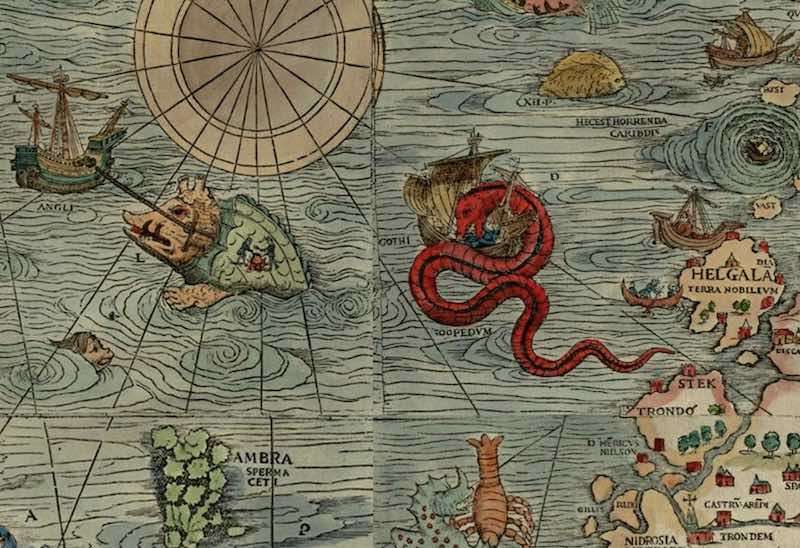

Near the coast of Norway, descriptions from sailors led to Magnus illustrating an image of a sea serpent attacking a ship, which in this case would be a mythical beast called a "sea orm", the inspiration for which scholars believe be whales, squids, sea lions, or more.

Magnus wrote in a later history that a sea orm could rear its head up out of the sea and pluck an unwitting sailor directly from his deck. He described it as being 200-feet long (double the size of a blue whale) and 20 feet in girth.

Whales are actually pictured on the map, identified by their Latin name balena, but Magnus' depictions hint at the original hypothesized appearances of these gentle giants. Seeming more like boar than balena, the whales sport long tusks and have two blowholes instead of one, appearing in place of a hog's ears rather than along the spinal column as is the case with whales. Two can be seen attacking ships off the coast of Iceland.

Accounts of mythical "sea swine" can be traced as far back as ancient Greece, but Magnus depicts them in the illustration marked ‘E' with webbed "dragon's feet" and a single eye down toward the beast's belly.

Another variation on the balena/boar beast is the prister, which was also 200-feet long according to Magnus, and could be scared away with the blast of a trumpet, of all things. Near Iceland in his Carta Marina, a sailor is depicted doing just this, while westward, a beast marked on the map as a "prister" rears up much like a sea orm, and apart from the blowholes/ears, seems quite serpant-like; and is covered in spines for good measure.

Chet Van Duzer, author of Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, spoke to Nat Geo about the map and said that nearly everything depicted on it was just variations on the same theme of terror and confusion inspired by whales, whether breaching, tail-slapping, or on occasions of striking wooden ships with their huge bodies.

Mortality of sailors on long-distance voyages was around 50% for much of the Age of Exploration, and while this was due mainly to scurvy and other diseases, the fact that so few mariners returned home stoked traditional fears of being gobbled up by a monster, and must have deeply informed Magnus' map.

The gorgeous colors and illustrations have made the Carta Marina a constant source of intrigue and delight for later scholars. Other depictions such as the sea cow, which could be thought to be a manatee but is shown on the map as a literal cow, as well as narwhals and walruses, all entice the history fan by providing a perfect glimpse into the behavior or beliefs of past generations.

SHARE This Amazing History Lesson And Map With Your Friends…

Be the first to comment