The Monster Waves at Nazare, Portugal

Every year, thousands of people visit Nazaré - Portugal to see big wave surfers ride the world’s biggest waves.

As I trekked through Cappadocia's Love Valley, fierce winds stirred up dust, painting the air with loose soil. The landscape unfolded before me, with hillsides adorned in shades of pink and yellow, contrasting against the deep red canyons. In the distance, towering chimneystack rock formations added to the scenic beauty. Despite the arid, hot, and windy conditions, the landscape was undeniably breathtaking. Millennia ago, the region's volcanic activity shaped the surrounding spires into their distinctive conical forms, attracting millions of tourists who come to hike or take hot-air balloon rides in this central Turkish region.

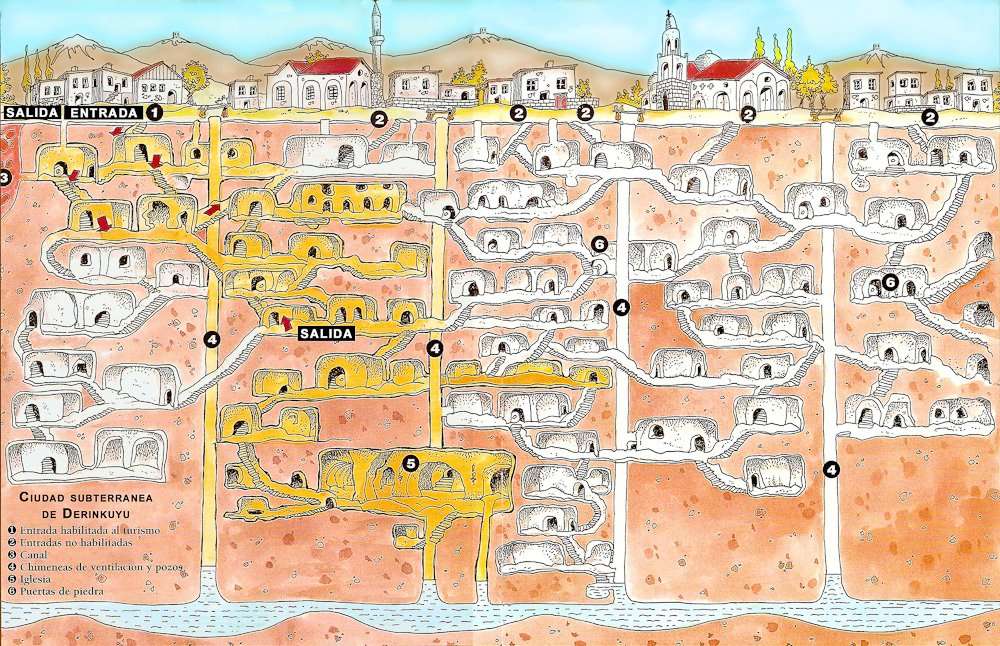

However, beneath the surface of Cappadocia lies an equally astonishing marvel—a subterranean city that remained hidden for centuries. This underground labyrinth could house up to 20,000 inhabitants, providing refuge for extended periods, concealed from the outside world.

The ancient city of Elengubu, now known as Derinkuyu, lies deep beneath the Earth's surface, descending over 85 meters and consisting of 18 levels of interconnected tunnels. As the largest excavated underground city globally, it remained in frequent use for millennia, passing through the hands of various civilizations including the Phrygians, Persians, and Byzantine Christians. Its abandonment in the 1920s came with the departure of the Cappadocian Greeks during the Greco-Turkish war, seeking refuge in Greece. Stretching for hundreds of miles, its cave-like chambers not only comprise Derinkuyu but are believed to connect to over 200 smaller underground cities in the region, forming an extensive subterranean network.

According to local guide Suleman, Derinkuyu's rediscovery in 1963 was accidental, spurred by a resident's recurring loss of chickens. During renovations, a crevasse appeared in the floor where the fowl disappeared. Further investigation revealed a hidden passageway, marking the first of over 600 entrances discovered within private homes leading to Derinkuyu's underground labyrinth.

Digging commenced promptly, uncovering a complex maze of subterranean residences, storage facilities for dry goods, livestock pens, educational spaces, wine-making areas, and even a place of worship. It represented a complete society sheltered beneath the ground. This underground settlement quickly became a popular destination for adventurous tourists in Turkey, and in 1985, the area earned recognition on the UNESCO World Heritage list.

The precise origin of the city's construction is still debated, but the oldest known written reference to Derinkuyu appears in "Anabasis," penned by Xenophon of Athens around 370 BCE. In this work, he describes Anatolian individuals residing underground in excavated dwellings, rather than the more common cliffside cave residences typically associated with the Cappadocian region.

According to Andrea De Giorgi, an associate professor of classical studies at Florida State University, Cappadocia possesses unique attributes that make it well-suited for underground construction. He notes that the soil's lack of water content and the easily moldable nature of its rock contribute to this suitability. De Giorgi explains that the region's geomorphology facilitates the excavation of underground spaces, with the local tuff rock being relatively easy to carve using basic tools such as shovels and pickaxes. Interestingly, this same pyroclastic material formed naturally into the picturesque fairy-tale chimneys and phallic spires visible above ground.

Cappadocia is uniquely suited to this kind of underground construction due to the lack of water in the soil and its malleable, easily mouldable rock

The exact origins of Derinkuyu's construction are somewhat unclear. The initial development of the extensive underground cave system is frequently credited to the Hittites. A Bertini, an authority on Mediterranean cave dwellings, suggests in his essay on regional cave architecture that the Hittites may have begun excavating the initial levels in the rock around 1200 BCE, possibly in response to attacks from the Phrygians. Supporting this theory is the discovery of Hittite artifacts within Derinkuyu.

Nevertheless, it is probable that the majority of the city was constructed by the Phrygians, who were adept Iron Age builders with the resources to create sophisticated underground structures. Andrea De Giorgi, elaborating on this, stated that the Phrygians were among Anatolia's prominent early civilizations. Emerging in western Anatolia towards the conclusion of the first millennium BCE, they had a penchant for monumentalizing rock formations and crafting impressive rock-cut facades. Despite being somewhat enigmatic, their realm expanded to encompass a large portion of western and central Anatolia, including the territory where Derinkuyu is located.

Originally, Derinkuyu likely served as a storage facility for goods, but its principal function was to offer temporary refuge from foreign invaders, given Cappadocia's history of enduring numerous dominant empires over the years. Andrea De Giorgi explained that the succession of empires and their effects on Anatolian landscapes led to the utilization of underground shelters like Derinkuyu. He noted that it was during the 7th century, amidst Islamic raids on the predominantly Christian Byzantine Empire, that these dwellings were utilized to their fullest extent. While various civilizations such as the Phrygians, Persians, and Seljuks inhabited the region and expanded upon the underground city in subsequent centuries, Derinkuyu reached its zenith population during the Byzantine Era, boasting nearly 20,000 residents living underground.

Today, you can delve into the immersive experience of subterranean life for a mere 60 Turkish lira (£2.80). As I ventured down into the dank, confined passageways, the walls darkened by centuries of torch smoke, an unfamiliar sense of claustrophobia crept over me. However, the resourcefulness of the various civilizations that expanded Derinkuyu soon became evident. Deliberately narrow and low corridors compelled visitors to maneuver through the maze-like network of tunnels and residences while hunched over and in single file—a strategic design to deter potential intruders. Illuminated dimly by oil lamps, massive circular stones, weighing half a ton each, obstructed entryways between the 18 levels, and could only be shifted from the inside. These formidable barriers featured small, precisely drilled holes at their centers, likely enabling residents to defend against invaders while maintaining security.

"Life underground was likely incredibly challenging," remarked my guide Suleman. "Residents used sealed clay jars for sanitation, relied on torches for illumination, and designated specific areas for disposing of deceased individuals."

Each tier of the city was meticulously planned for specific purposes. Proximity to the surface was reserved for stables to house livestock, strategically placed to mitigate odors and harmful gases while providing natural insulation during colder seasons. Further within the city lay residences, storage areas, educational facilities, and communal meeting spaces. Notably, on the second level, a distinctive Byzantine missionary school featuring barrel-vaulted ceilings, accompanied by adjoining study rooms, is identifiable. According to De Giorgi, the presence of cellars, pressing vats, and amphoras (tall, two-handled jars with narrow necks) serves as evidence of winemaking activities within Derinkuyu. These specialized areas suggest that the city's inhabitants were well-prepared to endure extended periods underground.

But the most remarkable feature of Derinkuyu is its intricate ventilation system and fortified well, crucial for supplying the entire city with fresh air and clean water. It's believed that the initial development of Derinkuyu prioritized these vital components. Over 50 ventilation shafts were strategically placed throughout the city to facilitate natural airflow between the various dwellings and corridors, safeguarding against potential threats to the air supply. Additionally, the well, extending over 55 meters deep, could be readily sealed off from below by the city's residents, ensuring their access to water remained secure.

While Derinkuyu stands out for its ingenious construction, it's just one of many underground cities in Cappadocia. Covering an area of 445 square kilometers, it's the largest among over 200 underground cities scattered beneath the Anatolian Plains. Over 40 of these smaller cities have depths of three levels or more beneath the surface. Several are interconnected with Derinkuyu through meticulously crafted tunnels, some stretching as far as 9 kilometers. Each of these cities is equipped with emergency escape routes in case a swift return to the surface becomes necessary. However, the subterranean mysteries of Cappadocia are far from fully uncovered. In 2014, a new and potentially even larger underground city was discovered beneath the Nevsehir region.

Derinkuyu's narrative reached its conclusion in 1923 with the evacuation of the Cappadocian Greeks. Over 2,000 years after its probable inception, Derinkuyu was deserted for the final time. Its existence faded into obscurity until a fortuitous incident involving wandering chickens brought the underground city back into the modern world's consciousness.

Be the first to comment