Arab Plumbers Refuse to Charge Israeli Woman After Learning She is a Holocaust Survivor

When these two brothers discovered that one of their 95-year-old clients was a Holocaust survivor, they refused to charge her a dime.

Scientists say an 11th-century Islamic astrolabe, bearing both Arabic and Hebrew inscriptions, is one of the oldest examples ever discovered, and one of only a handful known in the world.

They say the astronomical instrument was adapted, translated, and corrected for centuries by Muslim, Jewish, and Christian users in Spain, North Africa, and Italy where it was discovered.

Dr. Federica Gigante, of Cambridge University, first came across a newly uploaded image of the astrolabe by chance on the website of the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo, in Verona. Intrigued, she asked them about it.

"The museum didn't know what it was, and thought it might actually be fake," she told the press. "It's now the single most important object in their collection."

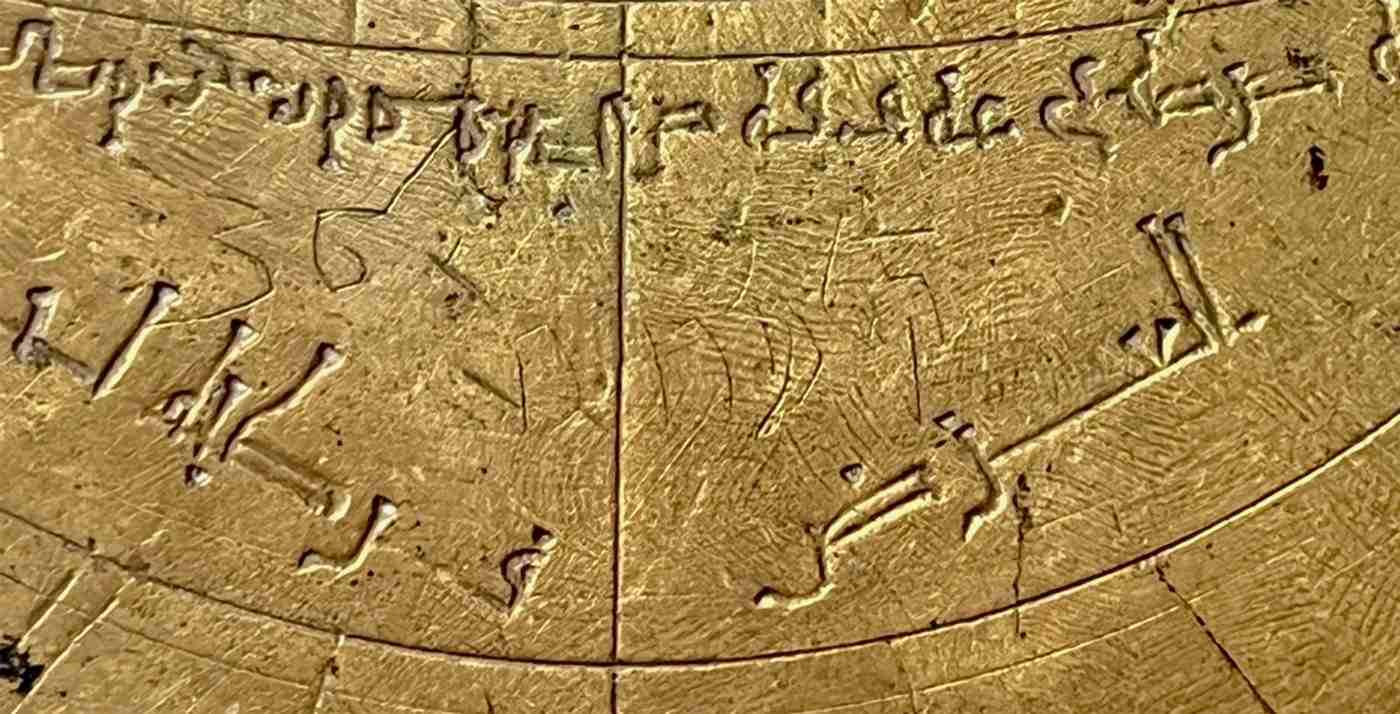

"When I visited the museum and studied the astrolabe up close, I noticed that not only was it covered in beautifully engraved Arabic inscriptions but that I could see faint inscriptions in Hebrew," she said. "I thought I might be dreaming, but I kept seeing more and more. It was very exciting."

Dr. Gigante is an expert on Islamic astrolabes and previously a curator of Islamic scientific instruments. She says astrolabes were kind of like the world's first smartphone, a computational device that could be put to hundreds of uses.

The instruments provided a portable two-dimensional model of the universe fitting in the user's hand, enabling them to calculate time and distances, plot the position of the stars, and even forecast the future by casting a horoscope.

She identified the object as Andalusian, and from the style of the engraving, and the arrangement of the scales on the back, matched it to instruments made in Al-Andalus, the Muslim-ruled area of Spain, in the 11th Century.

"The Verona astrolabe underwent many modifications, additions, and adaptations as it changed hands," she said. "At least three separate users felt the need to add translations and corrections to this object, two using Hebrew and one using a Western language."

"This isn't just an incredibly rare object. It's a powerful record of scientific exchange between Arabs, Jews, and Christians over hundreds of years."

One side of a plate is inscribed in Arabic ‘for the latitude of Cordoba, 38° 30′,' while the other side ‘for the latitude of Toledo, 40°.'

Dr. Gigante suggests that the astrolabe might have been made in Toledo at a time when it was a thriving center of coexistence and cultural exchange between the Abrahamic faiths. The astrolabe features Muslim prayer lines and prayer names, arranged to ensure that its original intended users kept on time to perform their five supplications.

The signature inscribed on the astrolabe reads in Arabic: "for Isḥāq […]/the work of Yūnus."

She said the two names Isḥāq and Yūnus—Isaac and Jonah in English—could be Jewish names written in the Arabic script, a detail that suggests that the object was at a certain point circulating within a Sephardi Jewish community in Spain, where Arabic was the spoken language.

A second, added plate is inscribed for typical North African latitudes suggesting another era of the object's life. It was perhaps used in Morocco, which hosted a large Jewish diaspora for centuries, and contains Jewish sites that today are still marked by pilgrimage and celebration.

Hebrew inscriptions were added to the astrolabe by more than one hand. One set of additions is carved deeply and neatly, while a different set of translations is very light, uneven, and shows an insecure hand.

"These Hebrew additions and translations suggest that at a certain point, the object left Spain or North Africa and circulated amongst the Jewish diaspora community in Italy, where Arabic was not understood, and Hebrew was used instead," said Dr. Gigante.

Other Hebrew inscriptions are instead translations of the Arabic names for astrological signs, for Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces, and Aries.

Dr. Gigante, whose findings were published in the journal Nuncius, says that the translations reflect the recommendations prescribed by the Spanish Jewish polymath Abraham Ibn Ezra in the earliest surviving treatise on the astrolabe in the Hebrew language written in 1146 in Verona, exactly where the astrolabe is found today.

Twelfth-century Verona hosted one of the longest-standing and most important Jewish communities in Italy, and Ibn Ezra warned his readers that an instrument must be checked before use to verify the accuracy of the values to be calculated.

Dr. Gigante suggests that the person who added the Hebrew inscriptions might have been following such recommendations.

The astrolabe features corrections inscribed not only in Hebrew but also in Western numerals. All sides of the astrolabe's plates feature lightly scratched markings in Western numerals, translating and correcting the latitude values, some even multiple times.

Dr. Gigante believes it is highly likely that the additions were made in Verona for a Latin or Italian language speaker.

In one case, someone lightly scratched the numbers "42" and "40" near the inscription reading ‘for the latitude of Medinaceli, 41° 30′,' though Dr. Gigante points out the original Arabic was actually more accurate for this latitude.

The astrolabe is thought to have made its way into the collection of the 17th Century Veronese nobleman Ludovico Moscardo before passing by marriage to the Miniscalchi family. In 1990, the family founded the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo to preserve the collections.

"This object is Islamic, Jewish, and European, they can't be separated," Dr. Gigante confirmed.

SHARE This Intercultural Treasure With Your Friends On Social Media…

Be the first to comment