As reported in an eye-opening new research paper, scientists have created tiny human livers out of human skin cells before successfully transplanting them into rats.

"What we are planning to do is to start making mini human organs that are universal," explained the paper's co-author, Alejandro Soto-Gutiérrez, from the University of Pittsburgh."That would change the paradigm of transplants".

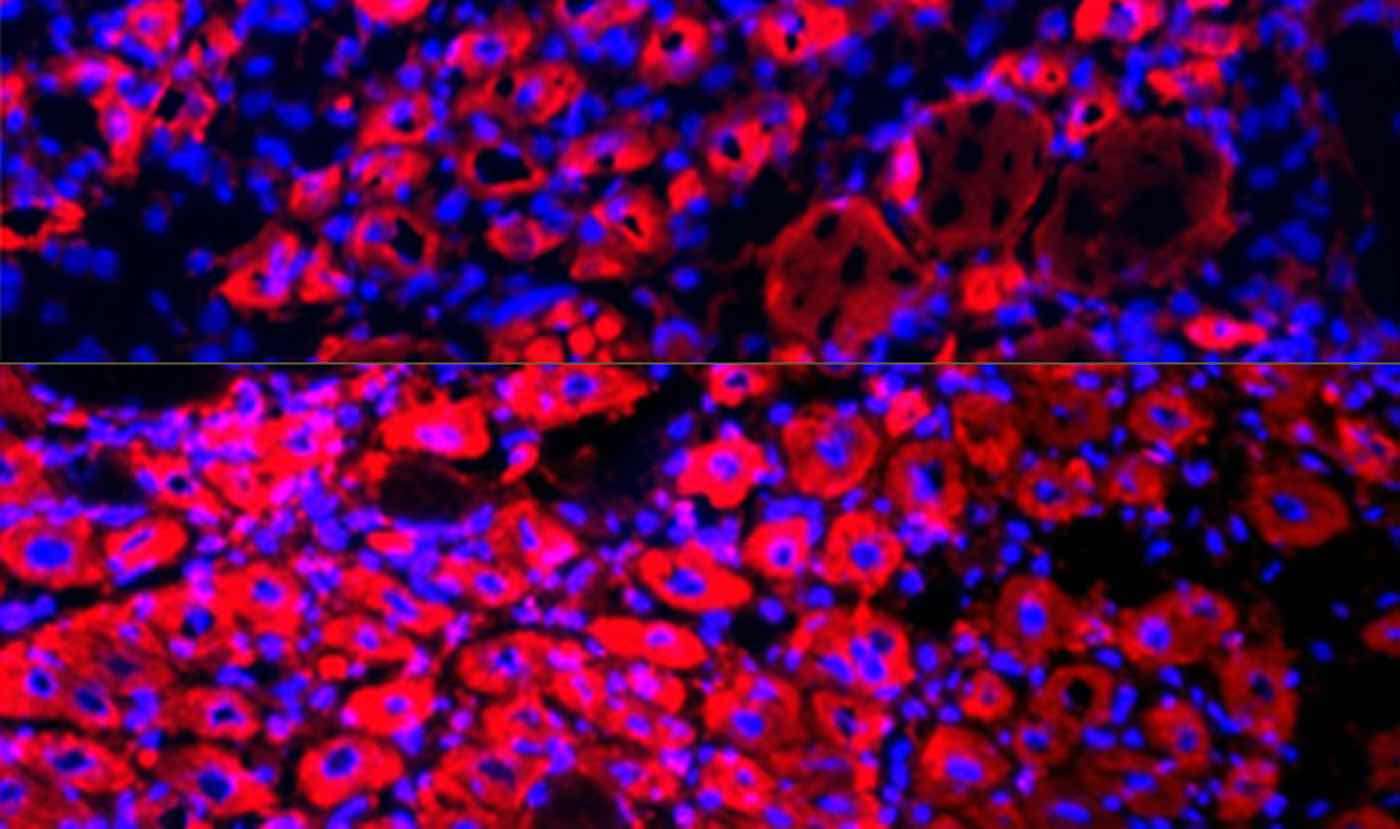

The science-fiction-like procedure was done by taking adult skin cells and genetically altering certain genes and transcription factors to create what are known as "pluripotent stem cells."

It starts with human skin cells called fibroblasts, in 2006 the pioneering field of genetic-editing led scientists to discover that they can simply take any cell from a living adult and turn it into a pluripotent stem cell.

"Pluri," meaning plurality, indicates its ability to carry the genetic code of all organ types, which is how they can become liver cells.

According to the Mayo Clinic, the number of people on current waiting lists for liver transplants far exceeds the number of available liver donors. The cost is just as high: the medical journal Inverse reports the average cost of a transplant, accounting for the entire procedure, is about $812,000.

New technologies always reduce the cost of existing products (remember how expensive flat screen televisions were?) and a new paradigm of made-to-order fabrication of organs would likely fulfill all the demand for transplants while lowering the cost at the same time.

As fascinating as it is a little unsettling, the science took a decade to perfect, but is far still from human trials. The tiny organs from human cells continued working normally after they were transplanted into rats bred to have suppressed immune systems – otherwise the body would reject the foreign organ.

The method and associated technology could produce part-time liver grafts, that could prolong the lives of people waiting on the transplant list.

"The long-term goal is to create organs that can replace organ donation, but in the near future, I see this as a bridge to transplant," Soto-Gutiérrez told Inverse. "For instance, in acute liver failure, you might just need a hepatic boost for a while, instead of a whole new liver."

(File photo by OPCW Laboratory in Rijswijk, CC license)

YOUR Friends May Be On The Waiting List For Good News—Share on Social Media…

Be the first to comment