Cancer Death Rate Has Dropped 25% Since 1991 Peak

Thanks to reductions in smoking and advances in early detection and treatment, fewer Americans are dying of cancer every year, with millions of lives saved.

Michigan State University researchers have discovered that a chemical compound, which could become a new drug, reduces the spread of melanoma cells by up to 90%.

The man-made, small-molecule drug compound goes after a gene's ability to produce RNA molecules and certain proteins in melanoma tumors, which causes the disease to spread. Up until now, few other compounds targeting this process have been able to effectively shut it down.

Scleroderma is a rare and often fatal autoimmune disease that causes the hardening of skin tissue, as well as organs such as the lungs, heart and kidneys. The same mechanisms that produce fibrosis, or skin thickening, in scleroderma also contribute to the spread of cancer.

Neubig's co-author Kate Appleton, a postdoctoral student, said the findings are an early discovery that could be highly effective in battling the deadly skin cancer, which is responsible for 10,000 deaths in the U.S. each year.

"Melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer with around 76,000 new cases a year in the United States," Appleton said. "One reason the disease is so fatal is that it can spread throughout the body very quickly and attack distant organs such as the brain and lungs."

Through their research, Neubig and Appleton, along with their collaborators, found that the compounds were able to stop proteins, known as Myocardin-related transcription factors, or MRTFs, from initiating the gene transcription process described above in melanoma cells. These triggering proteins are initially turned on by another protein called RhoC, or Ras homology C, which is found in a signaling pathway that can cause the disease to aggressively spread in the body.

The compound reduced the migration of melanoma cells by 85 to 90 percent. The team also discovered that the potential drug greatly reduced tumors specifically in the lungs of mice that had been injected with human melanoma cells.

Being able to block along this entire path allowed the researchers to find the MRTF signaling protein as a new target.

Appleton said figuring out which patients have this pathway turned on is an important next step in the development of their compound because it would help them determine which patients would benefit the most.

"The effect of our compounds on turning off this melanoma cell growth and progression is much stronger when the pathway is activated," she said. "We could look for the activation of the MRTF proteins as a biomarker to determine risk, especially for those in early-stage melanoma"—and thus, effectively block the cancer's migration.

According to Neubig, if the disease is caught early, chance of death is only 2%. If caught late, that figure rises to 84%.

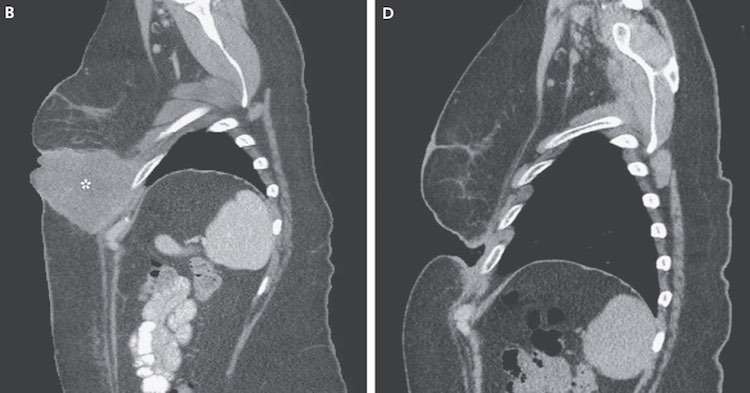

(Source: Michigan State University – Photo by New England Journal of Medicine)

SHARE the Good News – OR,

Be the first to comment