Galaxy Twinkling with Universe's Oldest Stars Discovered by Astronomers

Named the "Sparkler," it's a "globular cluster" nine billion light years away, just 4.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

Notorious plastic bags and containers can finally be upcycled, thanks to a new technique for recycling polyethylene bags and food packaging into valuable starter materials for high-value plastics and chemicals.

Polyethylene plastics are used to make plastic bags, shampoo bottles, and many products that are extremely difficult to recycle. In fact, only 14 percent of all polyethylene plastic are currently able to be recycled—and, then, only for certain products such as garden furniture.

They make up about one-third of the entire plastics market worldwide—all manufactured using massive amounts of fossil fuels.

But this may be changing thanks to scientists at the University of California, Berkeley in the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

They have found a way to break the sturdy polymers into the three-carbon molecule called propylene—a valuable molecule that can then be used to make new plastics, including polypropylene, which is used in ropes, twine, tape, carpets, upholstery, clothing, and camping equipment.

Not only that, the discovery will allow them to do it with very minimal fossil fuels.

"You can't take a plastic bag and then make another plastic bag out of it with the same properties," said John Hartwig, UC Berkeley Chair in Organic Chemistry. "But if you can take that polymer bag back to its monomers, break it down into small pieces and repolymerize it, then instead of pulling more carbon out of the ground, you use that as your carbon source to make other things — for example, polypropylene."

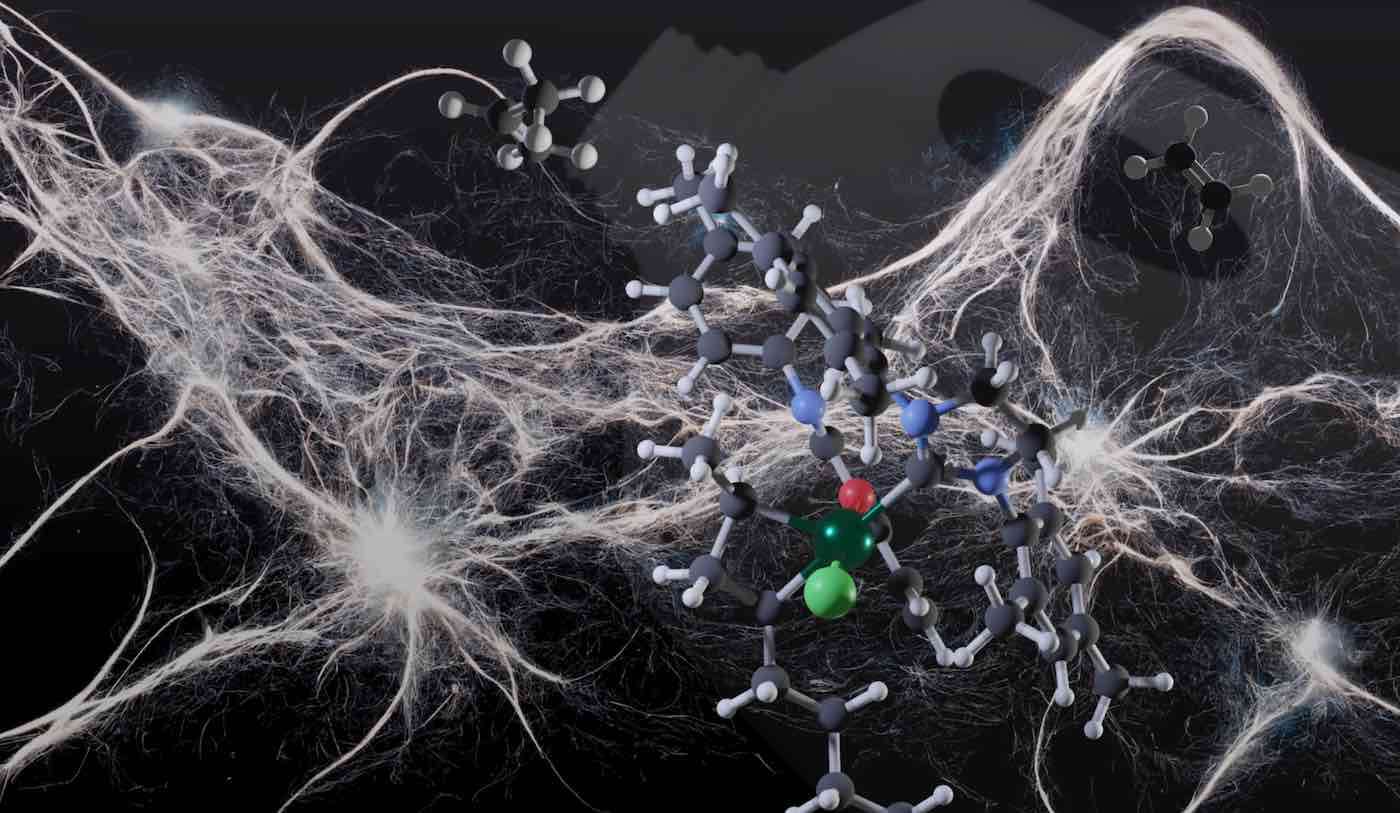

Polyethylene is held together by unusually unreactive carbon-carbon bonds that are very hard to break. In the breakthrough experiment, Hartwig and his team dissolved samples of HDPE (high-density polyethylene), the plastic used in container tops, milk jugs, and shampoo bottles, with ethylene gas and a catalyst in a solvent in a pressurized vessel.

These conditions, the researchers predicted, would force hydrogen from some of the monomer units. Such hydrogen loss, they reasoned, would in turn enable a series of reactions between the dehydrogenated polymer and ethylene in the presence of additional catalysts to produce propylene.

"I was pretty shocked that it worked so well," exclaimed Hartwig.

To the researchers' surprise, even though hydrogen was removed from just 1.9% of the monomer units, 87% of the carbon atoms in an HDPE polymer chain reacted with ethylene and became propylene in a mere 18 hours. This means that every other monomer in a chain of 1,000 monomer units turned into propylene gas – in other words, there was no polymer left.

The team reports in the journal Science that this form of upcycling could produce high value products, meet the high demand for propylene, give wasteful products a new purpose, and reduce the use of fossil fuels.

Hartwig said that although the technique is not yet ready for deployment at an industrial scale, their findings, supported by the US Department of Energy, have important implications for recycling polyethylene plastic into industrial lubricants and jet fuels, too.

In future experiments, he and his team plan to improve the technique's commercial viability with recyclable catalysts. They would also like to use this work to lay the groundwork for designing new types of chemically recyclable plastic.

UPCYCLE This Good News for Eco-Warriors on Social Media…

Be the first to comment