Here's Some Hope: People Have Lasting Immunity To COVID-19, Even After Mild Cases

Nature and Medrxiv studies on COVID-19 immunology indicates memory T-cell response and cross-protection, giving long-lasting immunity.

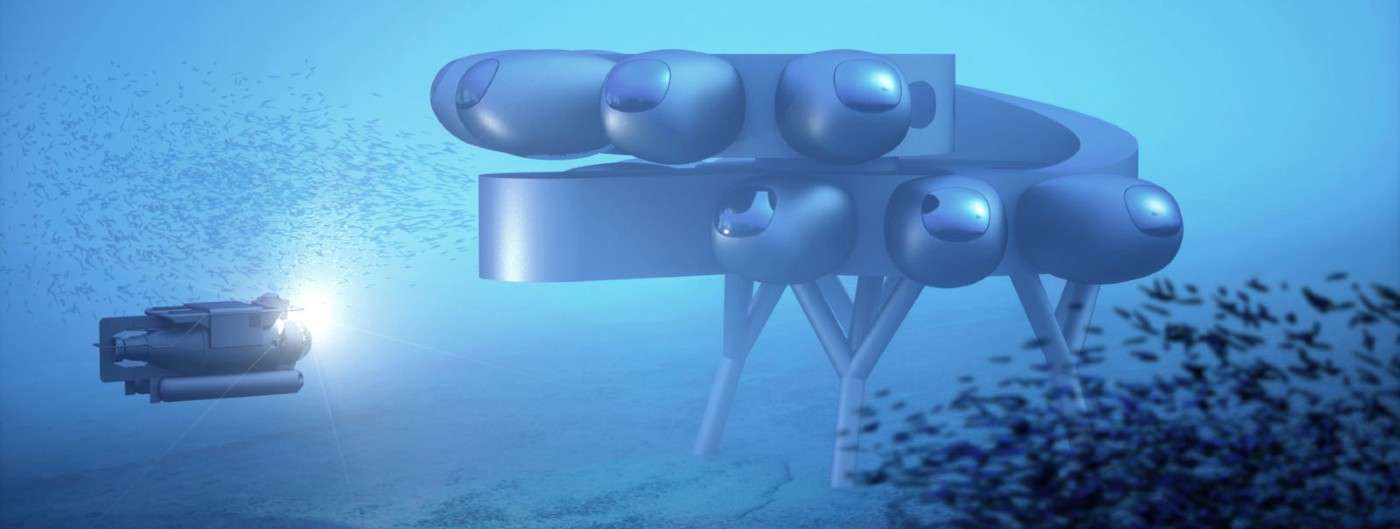

Inspired into action by the limitations observed after a month-long stay in the only remaining underwater research station, the Aquarius Reef Base off the coast of the Florida Keys, his new project would create the first modern undersea research base in over 30 years.

Called Proteus, it would be 4,000 square feet—a space ten times that of Aquarius, and one where biology and oceanography research would blend with climate and even pharmaceutical sciences to help create a more modern understanding of our oceans.

Fabien is every inch his father and grandfather. An oceanographer, environmental advocate, and "aquanaut," he learned the invented trade of his grandfather—scuba diving, when he was only four years old. Yet Fabien, now 52, is fed up with the limits of scuba as a research tool.

Confronted with the restrictions of time and depth, he sees Proteus as a chance to "have a house at the bottom of the sea, [where] we're able to go into the water, and dive 10 to 12 hours a day to do research, science, and filming."

Inspired into action by the limitations observed after a month-long stay in the only remaining underwater research station, the Aquarius Reef Base off the coast of the Florida Keys, his new project would create the first modern undersea research base in over 30 years.

Called Proteus, it would be 4,000 square feet—a space ten times that of Aquarius, and one where biology and oceanography research would blend with climate and even pharmaceutical sciences to help create a more modern understanding of our oceans.

Fabien is every inch his father and grandfather. An oceanographer, environmental advocate, and "aquanaut," he learned the invented trade of his grandfather—scuba diving, when he was only four years old. Yet Fabien, now 52, is fed up with the limits of scuba as a research tool.

Confronted with the restrictions of time and depth, he sees Proteus as a chance to "have a house at the bottom of the sea, [where] we're able to go into the water, and dive 10 to 12 hours a day to do research, science, and filming."

Proteus, named after the old Greek god of rivers and oceans, would sit 60 feet down off the coast of Curaçao, the island in the Lesser Antilles. Architect and industrial designer Yves Béhar and Fabien are looking to raise $135 million for construction.

"It will be a platform for global collaboration amongst the world's leading researchers, academics, government agencies, and corporations to advance science to benefit the future of the planet," reads the introduction to Proteus on the website for Fuseproject, Béhar's design firm.

Inspired by Jules Verne, Béhar envisioned that the station would consist of two large disks, one atop the other, connected by a spiral ramp. The edges of the disks would be lined with pods where bedrooms, bathrooms, and laboratories could be added.

At the center would be a social space above what Jacques Cousteau called a "liquid door" also known as a moon pool—a pressurized chamber where resident aquanauts could more rapidly set out for a dive.

The outside would be covered with artificial reef material to encourage habitation by neighborly sea-dwellers, and Fabien imagines a full-scale video production facility so that he, like his grandfather, can educate the world about the oceans' depths in real time; offering an unparalleled opportunity to educational institutions world-wide.

According to some estimates, only 80% of the ocean's territory has been mapped. Furthermore, the 20% that is recorded is often so unspecific as to miss the spires of undersea volcanoes, or airplane wreckage.

With Proteus, Fabien would be able to map a certain radius of the surrounding area to a resolution of a quarter inch, allowing scientists working there to study the changes in a rich marine environment in extreme granularity.

According to scientists speaking with Smithsonian Magazine about Proteus, one of the problems aquanauts and oceanographers have had to face over the histories of their professions is that the ocean often changes faster than they can make record of it.

"Studying the historical responses of ecosystems like coral reefs to past changes in climate provides a useful guide," says Brian Helmuth, a professor of marine and environmental sciences and public policy at Northeastern University, to Smithsonian.

"It [Proteus] would allow scientists to study the undersea environment by becoming a part of it, rather than working as casual interlopers."

Finally, as humanity begins working towards a new relationship with the planet, one of total command, yet total respect, undersea laboratories can help discover new species, understand how climate change affects the ocean, and allow for testing of green power, aquaculture, creating a picture of how humans might create, what Jacques Rougerie, a French underwater architect described as a "blue society."

It's Not Hard To Sea That You Should Share The Exciting News With Your Friends On Social Media…

Be the first to comment