She was Demoted, Doubted and Rejected But Now Her Work is the Basis of the Covid-19 Vaccine

The Hungarian chemist Katalin Karikó is being talked about for the Nobel Prize through her work on the mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine.

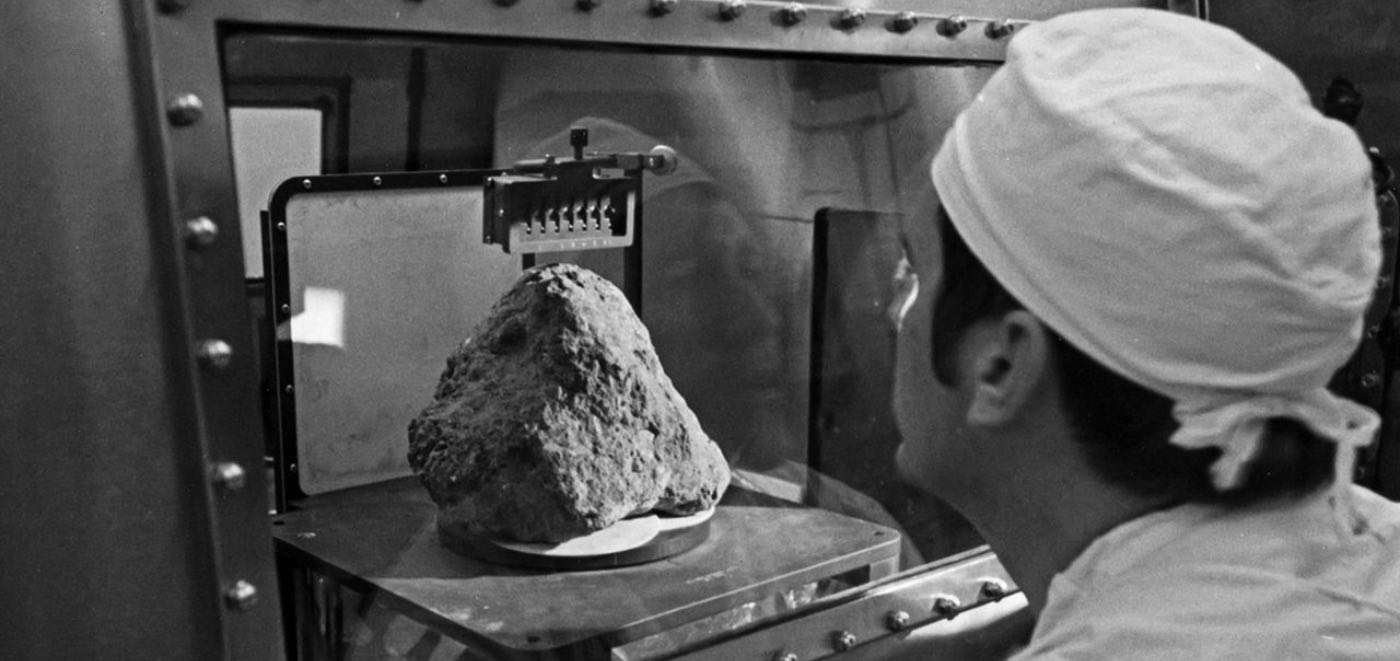

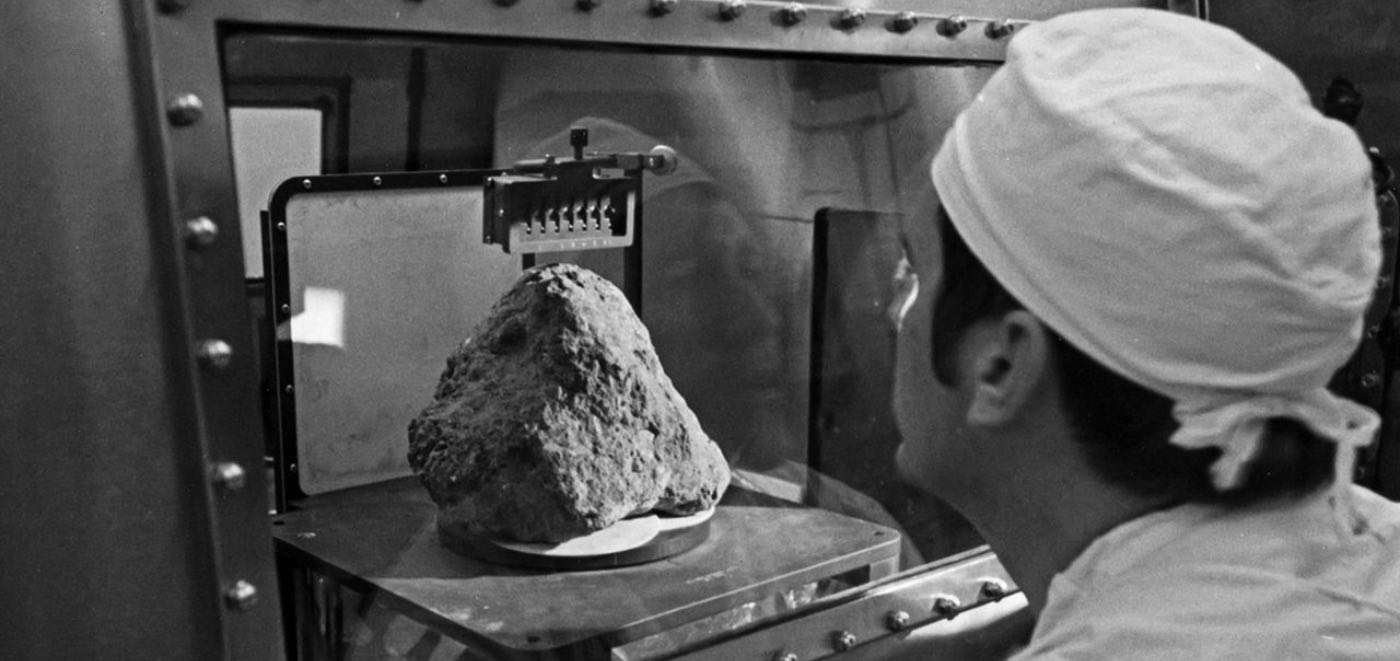

A rock taken by the Apollo 14 astronauts in 1971 from the surface of the moon was just determined to be merely a tourist-not a resident-of our nearest cosmic neighbor.

Analysis of the conditions that formed part of this 20-pound stone suggests that, rather than being a new kind of moon rock, it actually arrived from the Earth-tossed up into outer space by an asteroid impact over 4 billion years ago.

If the dating that placed its birth around 4.011 billion years ago is correct, it would actually be the oldest piece of intact Earth rock ever found, supplanting some erroneously dated mineral sand from Australia.

Many of us are familiar with the idea of pieces of planets and comets landing and falling to Earth, but Jeremy Bellucci at the Swedish Museum of Natural History may have just found the first "terrestrial meteorite," demonstrating that like a boxer, the Earth can take them as well as give them back.

According to Bellucci's paper, published in the journal Earth and Planetary Sciences Letters, the rock either "represents pressure, temperature, and oxidation conditions not known [on] the Moon," or much more likely, represents the case of Earth-formed material that was catapulted up to our Moon during an impact event.

The rock, charismatically designated "14321," is a kind of rock called breccia, characterized by a collage of different kinds of minerals created during an older period, bunched together in little sections called "clasts," and stamped together into a single stone.

It was one of these clasts that led Bellucci and the other researchers to their strange conclusion. There was a small piece of bright mineral which contained zircon, a very hard and long-lived mineral, and analyzing it and the surrounding quartz drew strange conclusions about conditions which have never been known to be present on the moon, relating to pressures, oxygen levels, and heat.

Bellucci, according to National Geographic, compared the zircon in 14321 to zircon on Earth and the similarities became clear.

"It was dead in the middle of the terrestrial field, and then I was like, Whoa… that's awesome!" Bellucci told National Geographic in an email correspondence. "From there, it snowballed."

The authors, who won't be able to expand on this breakthrough due to the COVID-19 pandemic, suggest that it will make a lot of people in museums and labs re-examine their moon rock samples.

ROCK OUT to the News With Your Friends-Share This Story on Social Media…

Be the first to comment