Instead of Putting Him in Nursing Home, Grandson Brings 95-Year-old WWII Vet on Epic Bucket List RV Trip

WWII veteran Johnnie Dimas was taken on an epic road trip to fulfill his bucket list by his grandson Roger Gilbert and wife Jo.

Clues as to the fate of the 115 men, women, and children of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island, the first English settlement in the New World, have been unearthed by archaeologists digging in a North Carolina field.

Teams of local as well as British archaeologists are working in several areas around Roanoke Island on a mystery that is one of the oldest in North American history.

Sir Walter Raleigh led an expedition of middle-class Londoners across the ocean to arrive at Roanoke Island off the coast of North Carolina in 1587. Shortly after they arrived, governor John White returned to England for supplies and to recruit more colonists, but a naval war between England and Spain prevented his immediate return.

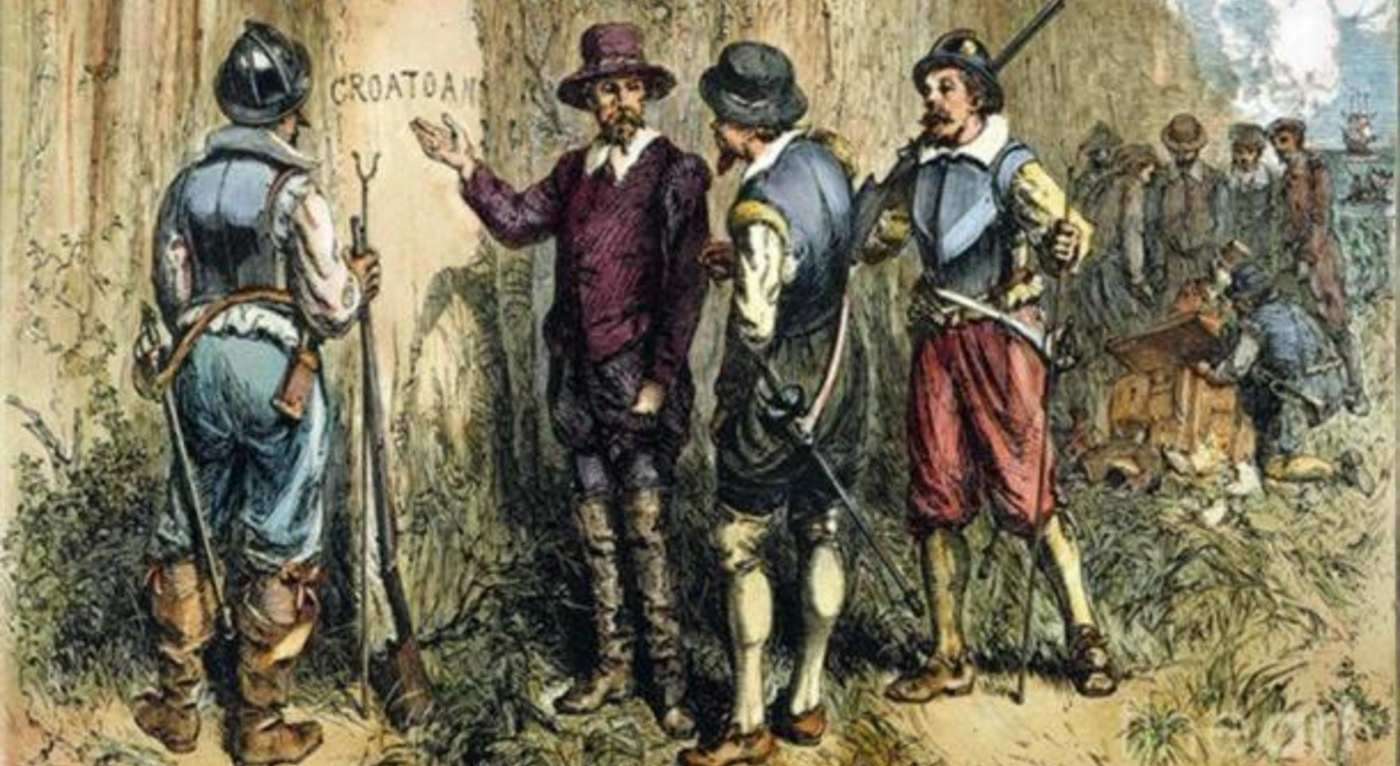

When he did get back he found the settlement in ruins and the people gone. All that he had to begin his own search was a single word, "Croatoan," carved on a wooden post in the middle of town.

Croatoan were names given to the place and people of modern-day Hatteras Island, about 50 miles south of Roanoke Island off the Outer Banks.

Governor White also wrote that the settlers intended to move 50 miles inland, close to native tribes they had befriended. A map drawn by White had a cloth patch over an area around 50 miles towards the interior on the shore of Albemarle Sound, with the outline of a fort drawn in invisible ink.

So we have settlers, mysterious names carved on posts, maps with hidden symbols, native tribes: no wonder it's one of the great archaeological mysteries of the colonization of the Americas.

In 2015, a team led by archaeologist Nick Luccketti excavated the site of the invisible ink-scrawled fort on White's map, aptly-called "Site X," and found two dozen shards of broken English pottery which he and his team maintain belonged to the Lost Colonists.

In January 2020, Luccketti returned to excavate about two miles north of Site X in a field which they called "Site Y," and found English crockery in much greater amounts, suggesting that—as has been observed in many colonial scenarios—order broke down for some reason, and colonists went their separate ways—evidently some moving just outside their Indigenous neighbors' village of Mettaquem.

Some archaeologists are skeptical that broken pottery shards are a good tool for dating the movements of the Lost Colony.

For example, Jacqui Pearce, a ceramic expert at the Museum of London, admits it's possible the shards could come from pottery made from the late 16th century and could have belonged to the colonists, but this English pottery's make and style carried on a long time, and it's just as possible they belonged to traders from Jamestown, settled two decades after the collapse of Roanoke.

Meanwhile, on the Island of Hatteras, or Croatoan as it was called in the Lost Colonists' day, European artifacts have been discovered in the remains of a Native American village, suggesting that between the three sites, it's very likely that some colonists, as White said, went 50 miles inland towards Site Y and X, and others went to Croatoan as scarred into the wooden post, as White also discovered upon his return.

William Kelso, the archaeologist who led the effort to discover the colony at Jamestown, says the three sites together "solve one of the greatest mysteries in early American history—the odyssey of the Lost Colony."

PASS This Treasure of a Story on to Friends on Social Media…

Be the first to comment